![]() FAQs about Adi Da & Adidam > Other Traditions > Adidam and Postmodernism: Part 2

FAQs about Adi Da & Adidam > Other Traditions > Adidam and Postmodernism: Part 2![]()

More on Adidam and Postmodernism

![]() This is Part 2 of Chris Tong's two-part article, Adidam and Postmodernism.

This is Part 2 of Chris Tong's two-part article, Adidam and Postmodernism.![]()

![]() FAQs about Adi Da & Adidam > Other Traditions > Adidam and Postmodernism: Part 2

FAQs about Adi Da & Adidam > Other Traditions > Adidam and Postmodernism: Part 2![]()

![]() This is Part 2 of Chris Tong's two-part article, Adidam and Postmodernism.

This is Part 2 of Chris Tong's two-part article, Adidam and Postmodernism.![]()

On viewpoints

There is much worth saying about the notion of "interpretations" (or "perspectives", or "points of view" — whichever term we may use), which is central to postmodernism.

Adi Da has spoken and written much about the limited points of view of the ego, and the necessity for transcending them by transcending egoity altogether. For example:

Avatar Adi Da Samraj, September 22, 2008 |

The limit of postmodernism is that it reduces everything to viewpoint. Thus it would suggest that what Adi Da is describing is just one more viewpoint, but one which is claiming to be "privileged". And if one buys into such reductionism, then one can get concerned (as do the postmodernists) about one "privileged" viewpoint declaring itself "king of the hill" over all the other viewpoints, and think of that as a kind of "fundamentalism".

But to presume all there is is (egoic) "viewpoint" is overly reductionistic — even though it is 99.9% correct, the only exception being the Enlightened person's (egoless) awareness. This is like Newtonian physics, which is an accurate approximation of physical reality 99.9% of the time, and whose limitations are found only in rather rare circumstances like the exact nature of Mercury's orbit: which requires general relativity to explain; or what happens to things that are very small: which requires quantum mechanics for an adequate accounting.

Another problematic notion of postmodernism is the complete relativity of all viewpoints. Let's consider this in the context of a simple example. That the earth goes around the sun or that an apple falls when you let go of it are illustrations of the law of gravity. This isn't "fundamentalism" — i.e., the law of gravity "lording" it over us! (as though it has intention, etc.); or the law of gravity claiming to be a more privileged viewpoint than the viewpoint that there is no such thing as gravity. It isn't "fundamentalism" to accept the law of gravity as a good approximation of physical reality. To think so would be to make a category error, confusing sociopolitical laws and physical laws. An apple falling is just an example of how things are. Now, our descriptions of how things are, and our current understandings of the laws of physics, etc. are viewpoints — that can vary among us, that can be refined (or thrown out) with time, etc. But all the while, the laws of physics are whatever they are (including even the possibility that they are not fixed, but change over time). And Reality Itself (the whole of what exists) is just what It is. Reality Itself is not a viewpoint. What exists is not a viewpoint. Descriptions of what exists are viewpoints.

But the literary types at the origin of the "post-modernist movement" sometimes get so pre-occupied with words, that they can forget that there really is a Reality that their words are pointing to, in addition to just "text" or viewpoint. Not only do they fail to "grok" the Zen admonition to pay attention to the moon, not the finger pointing to the moon (i.e., they fail to make the semiological distinction of "symbol" and "referent"); they even dismiss the reality of the Moon, and fixate all their attention on the fingers, proclaiming nothing but fingers exists!

The postmodernist view is that a viewpoint is anything which can be stated (i.e. put in language). I alluded earlier to the literary origins of the postmodernist movement, and (consequently) its founders' obsession with language (or the "text" or "narrative", as they refer to it). But to define "viewpoint" in a way that implies anything referred to by language is a viewpoint is tautological and completely lacking in discriminative capability, since — by definition (not by exhaustive examination) — everything we discuss is a viewpoint (because we are using words to discuss it).

Any notion of viewpoint which, by definition, dissallows anything from not being a viewpoint is pretty useless as a tool for discriminating between what is a viewpoint and what is not. "Everything is a viewpoint" is a religious or "fundamentalist" supposition in its own right. But there are other notions of "viewpoint":

“Point of view” is egoity. And “point of view” is also an action, not merely a fact. Going beyond that bondage, that limitation, is what the process of enlightenment is about. . . “Point of view” does not — and cannot — comprehend Reality. All its figurings are fundamentally false — or, at most, local, private, and ordinary. Adi Da Samraj, The Necessity of Meaning |

A far more pragmatic notion of "viewpoint" — i.e., one that actually allows for there to be something that is not a "viewpoint" — is one that harks back to the origin of the word itself. "Point of view" literally refers to the visual sense, and the fact that if you and I are standing at different positions in the room, looking at the same object, we will see different things because of our "viewpoint". We can use this as a much better source for a definition of "viewpoint", based on the insight that the perceptual senses (such as sight) are "filtering" or "creating" an interpretation of reality. A "viewpoint" — in this pragmatic sense — is a filtering or re-interpreting or re-presentation of reality, whatever reality is altogether. This definition of "viewpoint", unlike the tautological, postmodernist definition, admits the possibility of something that is without a viewpoint, namely, unmediated awareness of Reality Itself (whatever that is altogether) without any of the filters or interpreters.

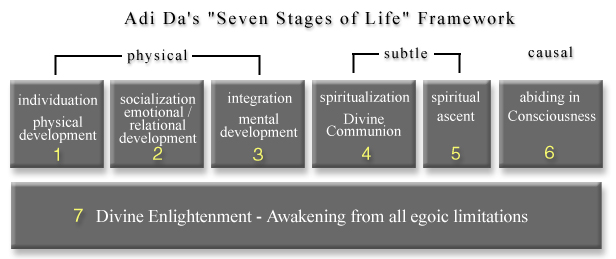

And indeed that possibility is at the core of Adi Da's The Basket of Tolerance. The primary organizational device for The Basket of Tolerance is Adi Da's notion of "the seven stages of life", which is based on the esoteric anatomy of human beings. To simplify this to our discussion, a human being has many levels of filtering (or "viewpoint") altogether. Some of it is occuring at the physical level, through the physical senses and the conceptual mind. But other forms of filtering are taking place on other non-material levels. The "soul" (to use common parlance) has its own perceptual and conceptual filtering mechanisms as it wanders about its non-material dimensions. And even the causal dimension of the human being filters reality through the mechanism of attention.

Adi Da's descriptions of the first six stages of life distinguish which spiritual and religious traditions are limited to which viewpoints, based on how practice of a given tradition's Way frees practitioners from the limits of certain filters (but not from others). Thus, a human being who has realized the astral dimensions (e.g., a saint or a yogi) might be largely free of the binding effect of the physical senses, because he or she is constantly aware of how "physical reality" is relatively peripheral compared to the subtle (or "heavenly") realms. But they are not free of the limits of the astral viewpoint.

Unlike His description of the first six stages, Adi Da's distinction between the first six stages and the seventh stage is a radical one, which does not fit into a "developmental sequence". The first six stages all have their own distinct and limited "point of view". The seventh stage is the Realization of the unmediated and unlimited "Point of View" of Consciousness Itself.

Adi Da has written an essay that outlines the "points of view" of the first six stages

of life, in contrast with the Realization of the seventh stage of life, which

is the transcendence of egoic "point of view" altogether:

From the point of view of the gross body, Everything Is Perceived, Conceived, and Presumed To Be An Irreducibly Material, Finite, Mortal Process. From the point of view of the mind, Everything Is Perceived, Conceived, and Presumed To Be An Effect, Made Of The Infinite Objective Substance Of Indestructible Cosmic Light, and Caused By the Infinite Totality Of Cosmic Mind. And Even The Totality Of Cosmic Mind Is, Thus, Presumed To Be Cosmic Light Itself. From The "Point Of View" Of Consciousness Itself, Everything conditional, objective, or Objectified Is Perceived, Conceived, and Presumed To Be Consciousness Itself, Such That conditional, objective, or Objectified Reality Is Inherently Realized To Be A Merely Apparent modification Of, In, and Upon The Native Radiance Of Consciousness Itself. Avatar Adi Da Samraj, "On Transcending the First Six Stages of Life" |

This is a description of the egoless "Point of View" of Consciousness Itself — unmediated by perception, conception, or even the limit on Consciousnessness that is attention — as "the Ultimate Viewpoint", in a radical sense: not the "endpoint" of some long (possibly infinite) developmental progression or evolutionary advance, but a radical shift to one's Native Viewpoint that is something like waking up from a dream.

This is not to say that someone who has Awakened no longer sees, hears, etc. It is just that their primary awareness is not as the limited body-mind but as Consciousness Itself, unmediated by perception, conception, and presumption.

The postmodern take on what we just said is: since we just described this in words, it's a viewpoint like any other. But this fails to distinguish between talking about something and Realizing something. Adi Da never used the postmodernist notion of "viewpoint" (anything that can be stated in text) — presumably because it is tautological and useless — and preferred the pragmatic notion (of viewpoint as reality filter or interpreter) introduced earlier, which is more consistent with His teaching about the seven stages of life. "Viewpoint" as we are describing it is not language but action. Stop the root action (which Adi Da calls the "self-contraction") that creates the sense of separate self, and limited egoic point of view is vanished. Unmediated awareness of Reality Itself is restored. Interpretation or filtering through the media of the body-mind is still there, but utterly peripheral.

"Realization" as a more useful term than "viewpoint"

In some sense, the word "Realization" (as used in spiritual traditions) is more useful than the word "viewpoint" because it doesn't get confused with language. Also people can all share the same fundamental Realization, while having many different viewpoints.

Thus these different Realizations (which have nothing to do with language per se) can be distinguished, and that is what Adi Da does in great detail in The Basket of Tolerance.

On what it means to be "self-evident"

There are all kinds of things we can say about Reality Itself, which could rightly be described as viewpoints. But that we are all appearing in Reality Itself (whatever that is altogether) is self-evident and self-authenticating, the same way our own existence is self-evident and self-authenticating, and need not be mediated by viewpoint, or described as a mere viewpoint.

Certain things are simply self-evident: like the way you know you exist. You can have different viewpoints about what exactly you are altogether. But that you exist is not in question. That's not a viewpoint — your own existence authenticates itself to you directly. Just so, that something or someone exists (or many "somethings" or "someones" exist, whether you view them as "many" or "one" or "objective" or "subjective" or "subjective-objective Conscious Light") is self-evident. (Or to express it conversely, "nothing exists" would be a viewpoint contradicted by our having this very conversation.) That whatever it is altogether — let's use the word, "Reality", to refer to the entirety — exists is self-evident. We may not be able to say (or agree on) what Reality is altogether (and whether it is objective or subjective, one or many), but regardless of our viewpoint, none of us can deny that Reality is. That is why Adi Da has defined "Truth" or "Reality" to be that which is always already the case (independent of viewpoint).

I mentioned that certain things are simply self-evident, like the way one knows one exists. Note that I am referring to one's mere existence, not any details about who or what one is altogether. So a baby, an ordinary adult, and an Enlightened person can all have very different experiences of (or viewpoints on) what they are, but what they all share is the immediate awareness that they are. It's just that in the case of the baby, it is an undifferentiated awareness (that hasn't yet carved out a separate "me", but obviously is expressing needs, has a universalized, pre-relational "me" with no boundaries, etc.); in the case of the ordinary (non-schizophrenic) adult, it's the usual, fairly well-defined sense of a separate self; and in the case of the Enlightened person, it is the centerless, boundless, awareness of Consciousness Itself.

And when I say "Certain things are simply self-evident, like the way you know you exist", I am not suggesting that, simply because something is self-evident, it is always evident to all of us in every moment. I am simply making the point that the means by which we know we exist (if and when we ever get around to using those means) is one that requires no thought, no perception, etc. — it is a direct awareness.

Some self-evident things are ones that all of us can easily verify right now — like the fact that we exist. Other self-evident things — like the Awakened State — require our going through a profound process, before we are "restored" to direct awareness of our Native State. But at that point, the reality of the Awakened State will be just as "self-evident" to us (i.e., available to us via direct, unmediated awareness) as our mere existence is self-evident to us right now. It is in this sense that Adi Da uses the term when He says (in the earlier quote) "Perfect Coincidence with the State of Reality Itself . . . is Intrinsic, or Tacitly Self-Evident". For Adi Da to describe something as "Self-Evident" does not mean it is presently obvious to all of us. It simply means that, when it does become obvious to us, it will be clear that its "obviousness" requires no thought, and not even any senses (physical or subtle) — it simply requires direct awareness.

And of course, Adi Da's capitalization of "Self-Evident" is crucial: the Awakened State is not self-evident to the egoic self. It is Self-Evident to the Divine Self. One must have transcended egoity altogether and be standing in the position of the Divine Reality for that Reality to be Self-Evident. Short of Divine Realization, we must at least be communing with the Divine Person in order for the Divine Reality to be tacitly evident.

|

Martin Heidegger |

The philosopher Heidegger (in his seminal work, Being and Time) suggested that one should in general be suspicious of most things being called "self-evident" (selbstverstandlich) — particularly those "self-evident" things that later turned out to be false! But his analysis of the notion of "self-evident" didn't stop there. He didn't just reject all notions of truth, like the postmodernists. He talked about the importance of a process of unconcealment (aletheia: literally, un-forgetting; recall Lethe, the river of forgetfulness) that would reveal the truth to a Dasein, one who cares about discovering the true nature of his being. Now Heidegger was a philosopher, not a Realizer; he could conceive of a process of unconcealment, but could not fully engage it (to completion) himself. In contrast, Adi Da, as a fully Awakened Realizer, is in a position to write a book, The Aletheon, giving every last detail of a process for completely unconcealing the truth, and revealing what is truly self-evident; and He is in a position to provide the means (the Way of Adidam) for all human beings to do so, being the perfectly authentic Da-sein ("Being-in-the-world").

On psychophysical reality, co-creation, and the Unconditional Reality

When we mentioned the "laws of physics" earlier, we intended it to be a simple, accessible example, aimed at cutting into the extreme (and absurd) view (taken by some postmodernists) that all viewpoints are relative or arbitrary. Patently, they are not! If I hold an apple up and let go, it is going to fall. If you do the same, the same thing will happen — regardless of there being other viewpoints in which we could imagine the apple will just float there without falling. The advantage that the scientific method has over postmodernism is its ability to take its viewpoints (or "hypotheses") and test them against Reality (whatever that is altogether). Postmodernism doesn't even admit that such testing is possible.

Now this is a very simple example. "Physical laws" are by no means an adequate description of Reality. They just provide ready-to-hand examples of how arbitrary notions of co-creating the universe are absurd. Adi Da views conditional reality as a mind-realm, and the laws of that realm as "psycho-physical", rather than merely physical. So if, for example, not you or I but someone with telekinetic powers lets go of that apple, perhaps the apple might not fall! And that's because the total picture includes not only the mass of the apple and the force of gravity, but any psychokinetic influences in the neighborhood as well.

Just to complicate matters, it's also true that the laws of physics (or psycho-physics) can change over time. But the reason the laws of physics appear to be a good approximation to the way things work is because the "co-creation" many "New Age" philosophers like to refer to (in the manner of an unlimited potential) is, in practice, extremely limited. We are not capable of altogether refashioning the universe just by an act of will! I'd be impressed if you could just suspend that apple in the air, let alone personally change the laws of physics permanently. As Adi Da once said, yes, we are all "gods" and "goddesses", co-creating this universe together. But since all of us are co-creating conditional existence together (including beings with immensely greater creative power than us human beings), each of us has relatively limited psycho-physical impact on the whole. That's why we can talk of "the laws of physics" as reasonably good approximations of how things work in this corner of the psycho-physical universe, for the near-term future. Those "laws of physics" are describing the relatively stable (or, of you prefer, relatively stuck or rigid) patterning we've all co-created.

Now, so long as one is identified with a body-mind, one is going to have a viewpoint. But Adi Da's communication is that being identified with a body-mind is not the only option. One can be identified with Consciousness Itself, and not have any limited, egoic, or separative viewpoint whatsoever.

Just so, note that we mentioned that Adi Da views conditional reality as a mind-realm. Our knowledge of (and our viewpoints on, and finally, our co-creation of) conditional reality are likely to evolve over the coming centuries (even as they obviously have in the last couple of millennia). But that evolution only applies to conditional reality, not to what Adi Da refers to as Unconditional Reality — That which is "always already the case" and unchangeable. By its very nature, Unconditional Reality is not subject to co-creation or change.

Distinguishing "referrer" from "referent" does not imply an objective reality

Earlier we mentioned the Zen admonition of being careful not to mistake the finger pointing

at the moon for the moon itself. We used this as an analogy for language and what

it refers to. There is the word, "moon", and then there is the actual

moon (whatever that is altogether).

Earlier we mentioned the Zen admonition of being careful not to mistake the finger pointing

at the moon for the moon itself. We used this as an analogy for language and what

it refers to. There is the word, "moon", and then there is the actual

moon (whatever that is altogether).

One common misunderstanding by people who subscribe to postmodernist thinking is to reduce everything to language, and to deny any "actual" anything, as though, in so doing, they would be admitting that there is an "objective reality". Modernist thinking distinguishes a word (the "referrer" or "signifier") from what it refers to (the "referent" or "signified"), and reality is understood to reside in the referents. But for postmodernists, the idea of any stable or permanent reality disappears, and with it, the idea of referents. For postmodernists, there are only surfaces, without depth; only referrers, without referents.

But

distinguishing a word from what it refers to does not imply an objective reality.

It is important to acknowledge the Reality that words describe as something distinct

from the words themselves, regardless of whether Reality turns out to be objective,

subjective, or even a non-dual unity of subjective-objective ("Conscious Light",

as Adi Da describes it). And that's why we add that phrase, "whatever that is

altogether" when we refer to Reality — to make it clear that we are not

introducing any philosophical presumptions (such as: Reality is objective).

The inherent limitations of language in describing that which is Unlimited

Just as it is important to distinguish referrer from referent, similarly, Adi Da's Ultimate Realization doesn't suddenly degenerate into "a mere viewpoint" simply because He chooses to use language to write about It. There are certainly inherent limits in the language itself when an Enlightened Being attempts to describe His Realization through language.[1] But those limits are the limits of the instrument, of the language, not the limits of the Realization.

And that is the real significance of the opening line of Lao Tzu's Tao Te Ching: "The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao". Just so, a philosophical system like postmodernism that is completely preoccupied with narratives, text, and viewpoints, cannot be the eternal Tao.

* * *

A shovel is a useful tool! It allows one to go below the surface. But it's also good to know when you hit bottom, and don't need to keep digging — and when you may need to switch to a different kind of tool. Postmodernism is, in some sense, a "one tool" philosophy (or "one trick" pony): it's great at "shovelling" (i.e., criticizing, deconstructing, relativizing, etc.), but it doesn't have the means to do much else. (It doesn't recognize a "bottom" in depth, e.g., like the "Ultimate Reality" of Adidam, dismissing such a thing as a typical "grand narrative" or a claim at a "privileged viewpoint".)

|

Umberto Eco |

It is sometimes suggested about professional critics of any kind that they represent not only a competence in criticism, but a lack of competence in creativity. In this spirit, the writer and semiotician, Umberto Eco, humorously caricatured (in his postscript to The Name of the Rose) the self-defeating, postmodern fixation on the merely verbal as "that of a man who loves a very cultivated woman and knows he cannot say to her, I love you madly, because he knows that she knows (and that she knows that he knows) that these words have already been written by Barbara Cartland."

Adi Da's literature and postmodernism

Askold Skalsky, a professor of English and a devotee of Adi Da, writes about the limits of postmodernism (in the context of commenting on Adi Da's literary opus, The Orpheum Trilogy), and how Adi Da provides a radical perspective and a Way for transcending these limits:

Cultural critics often try to make sense of the present moment of global turmoil by employing strategies of modern literary theory, which sees the blurring of boundaries between literature and modes of discourse in non-literary areas. In this view, human beings are “story-telling animals” depending on the logic of narrative for their most important actions and attempts at generating coherence and constructing a meaningful universe. Yet in postmodernity’s drive toward total openness, freedom, and a context in which all values are questioned, there is no longer adherence to any stable foundational truth but only competing narratives in constant collision. Macro-narratives like globalization and consumerism are in conflict with micro-narratives of local cultures or long-established values, and all of them in competition with other narratives ranging from national and ideological issues to personal and everyday ones. Consequently, the world is seen as a set of narrative texts reflecting the beliefs of human beings organized into institutions powered by competing ideologies of every shade and subject to close reading with the aim of exposing operations of power at all levels of society, leaving us with the fundamental predicament of postmodernity as the difficulty of living with difference and diversity in which fear of the dominant and destructive certitudes of the past is palpable, and yet a longing for some kind of absolute still persists. At this critical world-moment, Adi Da Samraj (1939-2008) provides a radical perspective in his literary trilogy The Orpheum, showing that the presumption of a separate “I” is an illusory category that distorts human consciousness and very language itself by falsifying the prior unity of reality. In his call to understand humanity’s bondage to fictional self-identity and to transcend egoity’s destructive search for narratives of self-protection and self-satisfaction, he transforms the separative premises of both the language of narrative and the givens of experience, reconnecting them with reference to reality itself. His revelatory writing, which he calls a mode of Transcendental Realism, articulates with poetic power the liberation inherent in an understanding released from the constructs of fixed attention and separate point of view and capable of non-problematically addressing the dead end of the postmodern and post-human global conflict in which societies currently find themselves. Askold

Skalsky |

Adi Da's image-art and postmodernism

Gary Coates, another devotee of Adi Da and a professor of architecture, expresses a similar point in the context of Adi Da's image-art, and describes Adi Da's artistic intention as "complete liberation from 'point of view' itself":

Adi Da points out, however, that this Modernist revolt against perspectival consciousness was occurring within the context of two catastrophic world wars and a planetary process of civilizational collapse, rather than within a framework that allowed for the possibility of cultural renewal. Thus, rather than continuing to explore the liberating impulses of modernism, the last decades of the twentieth century saw the emergence of what has been called postmodernism, which in spite of some of its positive aspects, largely has devolved into a solipsistic, ironic and radically relativistic worldview which both expresses and gives rise to a spreading sense of nihilism and despair. As a result we now find ourselves living in a world in which there are no longer any master narratives or privileged “points of view” from which to understand or describe the irreducibly complex and ultimately mysterious reality in which we find ourselves. It is as if the culturally sanctioned world that has been in the making since the Renaissance has reached its reductio ad absurdum and is now in the process of deconstructing as both a desirable and viable cultural form and mode of consciousness. Thus, at the beginning of the twenty-first century it seems that all things are possible, everything is relative, and nothing has any intrinsic meaning. At the end of our centuries-long quest for individual freedom, material comfort, scientific certainty and technological control over nature, we have arrived at a condition in which all certainties, authorities and traditions are dissolving into a morass of irreducible relativity, with everything from the planetary ecology to the global economy spinning out of control. Reality not only seems to elude our grasp, but, in principle, seems to be ungraspable. It is within the context of this long historical process leading to our present environmental, existential and societal crises that Adi Da’s aperspectival geometric art must be understood. He summarizes our moment in time, as it relates to the purposes of his art, clearly and succinctly: “The old civilization idealized the ego, and it ended up with a world of egos destroying one another. That course, in fact, is still happening and must be stopped — but it cannot be stopped merely by force. A transformation of human understanding and of human processes altogether must occur — on every level, including the artistic level.” While noting the importance of their prescient spiritual intuitions and important artistic accomplishments, Adi Da also observes that the avant garde artists of the early twentieth century never fully succeeded in transcending “point of view”: ironically, they ended up preserving “point of view” by merely asserting the simultaneous presence of multiple points of view. In making his art, Adi Da’s intention is to fully realize what was only implicitly potential in the Modernist project: complete liberation from “point of view” itself. He describes his image-art in these terms: “The image-art I make and do is the intrinsically ego-transcending — and, thus and thereby, perspective-transcending, or intrinsically aperspectival — image-art that participates in (or egolessly coincides with) Reality Itself.” If the perspectival art of the Renaissance helped to initiate a spiraling trajectory of societal changes which eventually led to the modern and postmodern worlds, then, as Adi Da asserts, a truly “aperspectival, anegoic and aniconic” art is required for the creation of the new modes of perception and understanding necessary for the next great transformation in consciousness and culture. As he says, his purpose is to contribute to just such an epochal change, “I am making art that is intended to be of greatest significance and transformative power — art that invites profound participation, rather than the mode of casual and dissociated viewing that allows and supports (and even requires, and, ultimately, even institutionalizes) mere ‘objectification’ and dissociative (or strategically non-participatory) detachment. I want to transform peoples’ participation in art — and also their participation in Reality (Itself, and altogether) — and help them to a new way of life, out of the “dark” period in which humankind is presently immersed.” Gary Coates |

RETURN TO "COMPARISONS WITH OTHER TRADITIONS"

![]()

Be the first to post a comment on this article. |