Adidam

and Music

The

best music draws attention directly to the Spiritual Reality. That is what makes

it enjoyable. Avatar Adi Da Samraj |

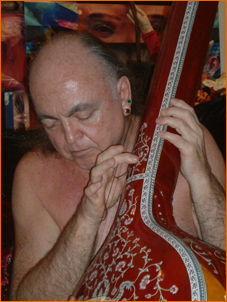

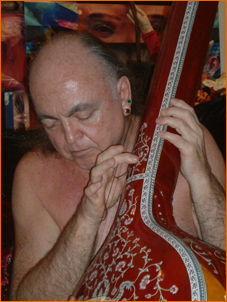

Ed. Note: Adi Da playing the tamboura (in the above picture)

is one of the rare occasions where He "used His own hands"

to play music (rather than using

the hands of His musician devotees). The recording of this

extraordinary occasion is available on the audio cassette, Nada

Dhyananta. The CD, Da

Mahamantra, combines Adi Da's tamboura playing with His chanting

of one of the Mahamantras: "Om Ma Da".

This

section is about all the different roles music has played (and continues to play)

in Adidam. It is organized as follows: - Diverse

Devotional Music with a Common Inspiration

- A

Culture of Invocation

- Name and Mantra Invocation

- Chanting

as a Discipline

- Swadhyaya Chanting

- Ordinary

Chanting versus Kirtan

- Drawing Upon Traditional

Musical Genres and Creating New Ones

- Musical Settings

for the Poetry, Literature, and Leelas of Adidam

- More Examples of Adidam Music

- Sacred Offerings

and Chanting Occasions

- Music as Sacred Art and

Means for Growing in the Relationship to Adi Da

- Participate

in a Sacred Musical Occasion

1. The Restoration of a Culture of Sacred Music

Virtually

all music these days is secular in both character and purpose. We might listen

to it on our iPod to "escape" from the world around us. We might use

it to stimulate us: by itself, or as we work, eat, exercise, or have sex. We might use it

to channel and release pent-up emotions, or relieve stress, or help us fall asleep at night. Or it might be part

of a shared social context which might include participation through singing

or dancing that makes us feel a part of a social group (an ethnic or religious

group, a group dedicated to a social cause, etc.).

All these ordinary uses of music have their place in ordinary

life. But in many traditional cultures (and even earlier in the

history of Western civilization), music was not exclusively

(or even mostly) dedicated to materialistic or social purposes.[1]

It was primarily created to serve a higher purpose: a sacred purpose.

| The

aim and final end of all music should be none other than the glory of God and

the refreshment of the soul. Johann Sebastian Bach |

With

Bach, and composers previous to Bach, we can talk of the sacred, of music and

musical form that evokes some feeling of orientation to the Divine, and toward

an aesthetic expression that transcends mere human content. Haydn and Mozart are

transitional figures in an event in the West of historical significance. It was

the turning from a Godward culture to an ego-assertive culture, or from the sacred

to a secular culture. This kind of change could be seen in music, but it was also

seen in all of the arts, and also in politics and even in religion. In the West

this is so, and it is also becoming more and more true of the entire world. I

am here to serve in a time when the effects of this change have become potentially

devastating for the world as a whole. It is time to make much of the sacred, and

deal with the past with much more discrimination. Avatar

Adi Da Samraj

June 28, 1989 |

And so, to this end, Adi

Da has integrated sacred music in many different parts of the new culture of Adidam

that He has created. As you will discover throughout this section, the result

is an extraordinarily rich new musical tradition that supports a culture purposed

toward Divine Communion.

One

of [Adi Da's] great missions relative to human civilization is to restore the

deep purpose of art art in all forms: visual art, literary art, musical art,

architecture all of that can be made to support the life of resort to the Divine,

the life of Communion with the Divine. . . . He has encouraged all of His devotees

to create beautiful environments, to create beautiful music, to create beautiful

artistic works. One

of [Adi Da's] great missions relative to human civilization is to restore the

deep purpose of art art in all forms: visual art, literary art, musical art,

architecture all of that can be made to support the life of resort to the Divine,

the life of Communion with the Divine. . . . He has encouraged all of His devotees

to create beautiful environments, to create beautiful music, to create beautiful

artistic works.

Jonathan

Condit

(Adi Da's chief editorial assistant) |

Music is a cultural device to sensitize people to the physical and emotional dimensions of their existence, so as to realize

a feeling of balance and well-being. . .

Music is a way of tuning in to the elemental harmony of the natural world, and the process of music has its own laws, which are the subject of study

in a sacred culture. Fundamentally, the sacred process of composing and making music and the experience of listening to music should take place in the

context of a sacred culture. . .

Neither music nor any other art has anything directly to do with Divine Self-Realization. But, properly used, the arts serve

the sacred culture that is devoted to Divine Self-Realization. The highest and most proper use of the arts is to serve the

sacred culture of those who are devoted to Divine Self-Realization.

Avatar Adi Da Samraj |

2.

Devotional Music as a Regular Element in the Practice of Adidam

Music

moves the heart. This is well-known, even in non-spiritual culture. It is not

surprising, then, that music plays an important role in the culture of the Way

of Adidam (also known as "the Way of the Heart").

Music

works upon our nervous system, our feeling of life, and creates a symphony out

of our emotion. In other words, a summary of feeling is somehow gestured out of

us through the impact of music, whereas a note-by-note analysis of it would have

no meaning. You cannot somehow find out how music has that emotional effect. It

is more magical, more arbitrary, more free than that. It is not discursive and it is not picture-making. Music undermines your effort to make a picture. It also undermines your effort to make sense, to make meaning and order out of it. So you are left with what it is all reduced to when meaning and pictures are not your capacity. You are left with this emotional impact that seems profound and beautiful, but it is not reducible to meaning. It is reduced to the feeling that you cannot put on the page. Music

works upon our nervous system, our feeling of life, and creates a symphony out

of our emotion. In other words, a summary of feeling is somehow gestured out of

us through the impact of music, whereas a note-by-note analysis of it would have

no meaning. You cannot somehow find out how music has that emotional effect. It

is more magical, more arbitrary, more free than that. It is not discursive and it is not picture-making. Music undermines your effort to make a picture. It also undermines your effort to make sense, to make meaning and order out of it. So you are left with what it is all reduced to when meaning and pictures are not your capacity. You are left with this emotional impact that seems profound and beautiful, but it is not reducible to meaning. It is reduced to the feeling that you cannot put on the page.

Avatar

Adi Da Samraj

February 17, 1983 |

2.1.

Diverse Devotional Music with a Common Inspiration

Throughout the years (since Adi Da began the culture of Adidam

in 1972), the devotional music used for chanting or, more generally,

as a devotional expression of musically creative devotees, whether

used for chanting or not has been remarkably diverse.[2]

To a great degree, this is because Adi Da's approach to it was

an ongoing, highly experimental consideration, that continued

right up to His Divine

Mahasamadhi, and which His devotees continue now, after His

human lifetime.

The

music of Adidam draws upon many musical genres and instruments, from the oldest

to the newest, from the most traditional (tablas and didgeridoos) to the most technically sophisticated

(electronic synthesizers of all kinds).

| swadhyaya chanting with didgeridoos, tamboura, and harmonium

Da Love-Ananda Mahal |

Some

pieces are highly scripted, while others are improvisational. Some are contemplative,

while others are energetic, often depending on the context in which the piece

is being used. Some are set to words by Adi Da, while others contain lyrics written

by the composer. What do all these forms of devotional music have in common?

They all are devotional responses to the Divine Presence of Adi Da Samraj. For

this reason, Adi Da directed devotees in a wide variety of musical experiments,

to see what would actually work to magnify the devotional response to Him. Music

speaks for itself. For this reason, we've provided you with a few musical samples

in the following sections. Click the links marked  to hear the individual pieces. Or scroll down the page a bit and listen to them

all together, using our Music Player, to participate

in a Sacred Musical Occasion.

to hear the individual pieces. Or scroll down the page a bit and listen to them

all together, using our Music Player, to participate

in a Sacred Musical Occasion. These samples are just a small taste of all

the devotional music that has been created in Adidam over the years.

2.2.

A Culture of Invocation

Adi Da has described Adidam as "a culture of invocation".

The practice is all about recognizing and invoking Him in every

moment, ever more profoundly.[3] For

this reason, we always begin our formal cultural occasions with

a specific Invocation ("The First Great Invocation") and close with another

Invocation ("The Second Great Invocation" or one of the Sat-Guru-Naama

Mantras).

Because Adidam is a culture of Invocation, many of our musical

compositions are created as Invocations of Adi Da, as in the following example.

2.3.

Name and Mantra Invocation

In the great spiritual traditions, it was always understood

that reciting or chanting the Names of God or one's Guru had a

special "mantric" Force, beyond the communication of

the words themselves. Adi Da has confirmed this, and for this

reason, many of our chants focus on His Names, as a potent means

for Invoking Him.[7]

| [In the] Reality-Way of Adidam Ruchiradam,

chant, rather than song, is the principal mode of vocal Invocation of Me, or the

active exercise of worship in devotional recognition-response

to Me. In the Reality-Way of Adidam, chant is continuous Invocation of Me via

My Divine Avataric Names. Such Invocation steadies and purifies the body-mind-complex.

Avatar Adi Da Samraj |

The musical

style through which this is done can vary widely, as the following two examples

illustrate.

2.4.

Chanting as a Discipline

Adi Da's time in human form is

now over. But because He is eternally

present, the practice of devotional chanting to Him remains as powerful a

means as ever for serving the connection with Him and the magnification of devotion

to Him. Like all the other forms of whole bodily engaged devotional activity,

chanting serves the purpose of turning all the faculties of the body-mind (attention,

feeling, body, and breath) to Adi Da Samraj, in a single heart-based gesture of

devotional response:

|

Chant is simply the repeated Invocation of Me via the

Names and Mantras I have Given — while keeping the

psycho-physical faculties turned to Me. Therefore, chant

is among the fundamental daily practices for all of My

devotees.

Avatar Adi Da Samraj, The

Sacred Space of Finding Me

Physically

(and Formally) Engaged Sacramental Devotion Involves The

Externalization Of attention Via Intentional Activation

Of the body-mind (or frontal personality). In Contrast

To This, Formal (and Deep) Meditation Involves Progressive

Relinquishment Of physical and other outward-Directed

frontal activity. Generally, daily Practice Of The Way

Of The Heart Should Involve An Appropriately Balanced

(and Formal) Measure Of Meditative and outward-Directed

activities, but Even all outward-Directed activities Are

To Be Realized As Forms Of functionally Expressed Heart-Practice. Physically

(and Formally) Engaged Sacramental Devotion Involves The

Externalization Of attention Via Intentional Activation

Of the body-mind (or frontal personality). In Contrast

To This, Formal (and Deep) Meditation Involves Progressive

Relinquishment Of physical and other outward-Directed

frontal activity. Generally, daily Practice Of The Way

Of The Heart Should Involve An Appropriately Balanced

(and Formal) Measure Of Meditative and outward-Directed

activities, but Even all outward-Directed activities Are

To Be Realized As Forms Of functionally Expressed Heart-Practice.

Avatar Adi Da Samraj, The

Dawn Horse Testament

People

have to be instructed in devotional chanting in My Company. It is a means for

devotional Contemplation of Me, it is not a sing-along. It is a way to focus attention

on Me and invoke Me and open to and receive My Blessing. It is a devotional practice

of self-surrendering, self-forgetting, and, more and more, self-transcending feeling-Contemplation

of Me. Avatar Adi Da Samraj, August 2, 1993

True devotional chant

in the Reality-Way of Adidam is a practice that transcends the mind.

True devotional chant Invokes Me and turns to Me, and stays steady in that turning to Me.

Thus, in the Reality-Way of Adidam, true devotional chant is a mode of the moment-to-moment practice of whole bodily devotional turning to Me.

You must enter into that Divine Process through right and true practice, and through all the formalities that manifest the ecstasy of devotional Communion with Me.

Avatar Adi Da Samraj, The Sacred Space of Finding Me |

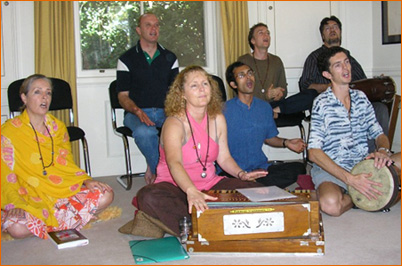

| Devotees

in Seattle, Washington chanting to Adi Da |

Chanting

is a form of practice of the Way of Adidam. You are not supposed to be chanting

to Me to provide a musical atmosphere or entertainment for Me. Chanting is not

done for My benefit. Chanting, like meditation, is a form of your sadhana, and, rightly done, it is a form of feeling-Contemplation

of Me. You do not chant to entertain or amuse Me. You chant as a means to feelingly

Contemplate Me. Chanting is not to be done self-consciously, as if you are

listening to your own voice. However, I have noticed self-conscious articulation,

obvious attention to correct pronunciation, and the attitude of performance. When

done properly, a chant is harmonious and it has an agreeable sign, not, however,

as a result of your being self-conscious about your voice. It is not even a matter

of your listening to the chant, since awareness of the chant is a very peripheral

aspect of chanting. You are not to be preoccupied with the musical or vocal aspects

of the chanting . . . I have also noticed that in some people, chanting

seems superficial. Some are just looking at the scene around Me. Attention in

them is scattered, and that is not the proper disposition for chanting. When you

are chanting, you should hold attention to Me, not staring at Me, but feeling

Me. If chanting is occuring in My physical Company, you should keep attention

on My bodily (human) Form. If it is not done in My physical Presence, then you

should keep attention on My Murti. Do not let attention, or mind, fall back on

the ego-self or wander. Avatar Adi Da Samraj, September 13,

1991 |

2.5.

Swadhyaya Chanting

Swadhyaya chanting — the musical recitation

of sacred texts — is both a longstanding tradition, and an important practice

in the Way of Adidam. Adi Da has emphasized many times that listening to His recited

Word can have a far greater (whole bodily) impact than simply sight-reading His

Word on the page (or the Web).

He also evolved a particular musical form

for swadhyaya chanting:

Traditionally

in India, the Guru

Gita and other recitations are sung in this manner of a very

simple, few-note melody in order to allow for a deeper reception of the Sacred

Text. . . . I've established (years ago) a format for that, for the chanting and

recitation of My Teaching Word. . . . that may have a repetitive, several line

form. Avatar Adi Da Samraj, April 27, 2005 |

The

specific musical "repetitive, several line form" with the "very simple,

few-note melody" used for swadhyaya chanting in Adidam is illustrated in the following

example.

2.6.

Ordinary Chanting versus Kirtan Devotional singing, particularly in

the form of kirtan, is particularly useful if one tends to be

"in one's head" (rather than being fully, whole bodily incarnated),

or if one has difficulty feeling.

If

you are too rigid to express your devotion to Me, you should be breaking through

that rigidity by engaging more in demonstratively expressive devotional practices

(such as pujas, full feeling-prostrations, chanting, and all the forms

of ecstatic devotional singing, including vigorous kirtan). . . . If you

are to transcend your presumptuous ego, you must animate your devotion to Me.

Devotion to Me is something you must do. Avatar Adi

Da Samraj

"Throw your body to the Floor, and Yield your Heart"

The

Love-Ananda Gita |

Adi Da distinguishes ordinary

chanting from kirtan in the following way:

There

is a difference between chanting and kirtan. Kirtan is when you use a song and

chant in a rhythmic, musical manner in which people are very active sometimes

rising up from their seat, dancing and jumping and spontaneously being moved.

Chant, on the other hand, is different. It is quieter in tone, and it is musically

less elaborate and less rhythmic. It is, instead, repetitive. It is made up of

repetitive lines, even words that are repeated over and over again called by a

chant leader. It does not, in general, suggest the kinds of responsiveness as

in a kirtan. It is not physically motivating. People, of course, may make sounds

or kriyas, but, in general, it is more calming. When chants are being done,

they should be done for an extended period of time repetitively, whereas, in kirtan

there can be several songs and chants done not in a repetitive fashion, for

brief periods of time. People look for chants to be bodily and vocally interesting.

The chanting mode is not interesting. It is calming and conducive to dropping

bodily and mental activity in a calmer sense. Avatar Adi Da

Samraj, March 26, 1992 |

2.7.

Drawing Upon Traditional Musical Genres and Creating New Ones

Adi Da

has always encouraged the musicians of Adidam to study and draw upon a wide variety

of devotional music traditions, as well as experiment with creating new musical

genres.

And

it's not just about imitating traditional modes of it either. If there are people

creative with music, they can come up with new forms unique to Adidam. Avatar

Adi Da Samraj, April 27, 2005 |

The purpose behind this

was not the conventional one of idolizing variety or novelty in art for its own sake. Rather,

the point was to study, learn from, and build upon time-tested means for magnifying

devotional expression; and to evolve new forms of musical expression most suited

to a new and unprecedented Spiritual Revelation.

The Indian tradition of sacred music — A significant

portion of the music of Adidam has been drawn from or inspired

by traditional Indian devotional chants and other forms of traditional

Indian music. Here are some examples.

Danavira

— In the experimental Adidam album, Danavira (The Hero

Of Giving), professional jazz composer, John

Mackay, drew from a wide variety of musical genres —

from Gregorian Chant to Christmas carols — in creating

new forms of Adidam devotional music. Danavira

— In the experimental Adidam album, Danavira (The Hero

Of Giving), professional jazz composer, John

Mackay, drew from a wide variety of musical genres —

from Gregorian Chant to Christmas carols — in creating

new forms of Adidam devotional music.

| Rejoice

— a choral piece that draws from the modern tradition of atonal choral works

(Charles Ives and others). | | |  | Interlude

— a short instrumental piece drawing on the classical music tradition, with

symphony clarinetist Bill Somers playing. | | | |  | There

Is Only Light — draws on the Qawwali tradition of Sufi devotional

music (exemplified by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan). Read Adi Da's appreciation of the

Qawwali musical tradition below. |

Jaya

— On another innovative Adidam album, Jaya,

the musicians experimented with taking traditional Indian devotional chants and

embedding them in the context of "world music". Facing East — The group,

Facing East, led by devotee, John

Wubbenhorst, continually experiments with new musical possibilities that often

seamlessly combine Eastern and Western musical traditions.  |  Facing

Beloved — From the album, Facing

Beloved, by group Facing

East, with John Wubbenhorst (bansuri), Subash Chandran (ghatam) and Ganesh

Kumar (kanjira). This piece is based on a melody from J.S. Bach (siciliano) with

elements of Raga Kirwani. |

2.8.

Not Getting with the Program (or self): Improvisation and self-Transcendence

in the Music of Adidam

Because the whole point of music in Adidam is

to magnify the devotional response to Him, Adi Da was always sensitive to when

the musical expression of devotees would become rigid, programmatic, "institutionalized", boring,

or automatic in its expression, undermining its purpose.

[In

1973, Adi Da and devotee Gerald Sheinfeld travelled

to India. These comments were from a period when they were visiting a traditional

Indian Ashram they are visiting.] Gerald Sheinfeld: The

first couple of days we attended all the chanting meetings, about four each day.

When we found out which of these were mandatory and attended only those. By the

end of the stay, Bubba [Adi Da] had stopped going to any chanting meetings. He

said that all this chanting was simply a form of "crowd-control." It was the external

representation of the internal sadhana of attention to God.

Adi

Da's further comments:

Chanting has its place as a moment, not as a

perpetual attempt to become absorbed. It is an occasion,

a pleasantry. It's enjoyable from a genuine point-of-view,

but once it becomes repetitive and constant, it is another

method. It should only be used to the degree that it is

natural, functional and appropriate.[6]

| |

[Adi

Da caricaturing devotees talking to each other:] "So what's on the program?

Do we get a Darshan now? What do we do in a Darshan?" "Well,

you bow down. You offer a flower. This is the routine. If you hear somebody chanting,

just imitate that." . . . . I do not want to be confronted by programs.

. . . That's not Adidam. It's not My Teaching. . . It's simply egoic behavior,

and it's taken on an institutional form. . . .That's what passes for a culture

of "Divine involvement" all over the world, in fact. That's what conventional

religiosity does. It creates these substitute performances that really do not

involve the transcending of egoity at all, that are making references to God or

Spiritual teachers or whatever, but they're not about anything at all. True

chant is something else. It's part of a devotional environment of profound contemplation

of Me, that's necessarily associated with a renunciate life. It can't be otherwise

because it's a different kind of concentration than what a non-renunciate life

is about. . . . When you see true devotion exhibited, it's a vision you

can't forget. . . [The singers'] practice has to coincide with the singing,

meaning it's got to be the sign of mature practice, true recognition

of Me, not just "you know how to sing". . . . So those who do chanting as

a service usually have not only training, but they have some disposition toward

it that at least has some level of authenticity. It doesn't mean it's the same

kind of depth motivation in every case, but of course, they have to serve the

gathering, to make the participation of others right, and not just a kind of sing-along.

Really, it's part of something that people should study in the gathering —

everyone. . . . There are "programs" in [other] Ashrams too,

different from place to place. There was a certain level of what you could call

"programs" at Baba Muktananda's Ashram in those early days [when

I was first there]. But it was rather loose in some fundamental sense also.

Avatar Adi Da Samraj

March 7, March 31, April 8, May 12,

May 16, and June 1, 2005 |

Because the ego so frequently falls into programmed behavior,

Adi Da sometimes encouraged musicians capable of it to engage

in musical improvisation — particularly when playing

music for Him — so that they could stay loose and open in

their feeling-expression. Based on recognition

of Adi Da as the Divine Person, such improvisation is, Adi

Da says, a kind of spontaneous "exclamation".[4]

Without such recognition:

.

. . they don't exclaim. They don't recognize Me. . . . It's formulas of speech.

. . . It's not recognition speaking [or singing, or playing] to Me. Avatar

Adi Da Samraj

April 12, 2005 |

Are you counting up

all My Sayings so you can remember what to do? I told you "It" Is My House. All you have to do Is

heart-recognize Me. And, the next thing you know, you Are in My House, singing to Me.

Avatar Adi Da Samraj

"The Concave Cube Of Normals To The Curve,

Or, A Horse Appears In The Wild Is Always Already The Case"

The Happenine Book |

Devotional, musical improvisation

in Adidam is always a matter of staying turned to Adi Da, and not falling into

either the pitfall of programmed musical expression or the pitfall of egoic

"self"-expression. Adi Da describes this second pitfall:

People

can get off the wall with [chanting], and self-involved and wrapped up in crazy

behaviors — that's possible too. Avatar Adi Da Samraj

May

17, 2005 |

Anciently,

all arts were forms of ritual. The artist submitted to a master of his or her

craft or art, by whom he or she would be schooled in the culture in other words,

the tradition, the limits, the techniques, the purposes of the art. By submitting

to this demand of the culture in general, the artist transcended his or her own

ego-possessed motivation. An artist was not permitted to paint, sing, or play

an instrument until the master could attest to the artist's preparation and affirm

that he or she was capable of serving the community, serving the culture. The

artist was capable of this because not only had he or she learned all the techniques

not only did the artist know how to awaken in his or her audience all the imagery

to which they were devoted and by which they might transcend themselves but

the artist had mastered himself or herself in the process. In modern time,

the arts have ceased to have a cultural purpose that is acknowledged to be necessary.

The arts become mere entertainments. The arts become ways of expressing

yourself, your contents, your insides your aberrations. In fact, the arts become

the very means for expressing the problems you have, because there is no culture,

no center, no society, no necessity to what you do the failure of the social

order, the failure of the demands within an artistic discipline that you transcend

yourself, that you master yourself, that you provide something within the social

order that is valued by others, that has intrinsic value, that has fundamental

value, that is not just decorative or entertaining, but that is part of the sacred

purpose of the community. Find a way to submit yourself to the function

of art within the true culture of Adidam Ruchiradam. That is how you will transcend

yourself in this process and make your art more than ego-possession, "self"-expression,

Narcissistic "self"-reflection. Find a way for your art to be ecstatic

and find some way for it to serve, even in ordinary ways. Give pleasure through

it and have that pleasure serve the appropriate mood of devotees. And then, perhaps,

find some higher purpose find a way for your art to be ecstatic in the Spiritual

sense. That is a discipline. Perhaps, it will take a long time to do that.

But one's struggle is not to fulfill oneself and make that "self" lovable

by the "world". The struggle is to transcend oneself in order to enter fully into

the Divine. Avatar Adi Da Samraj

September 17, 1980 |

You

can tell when improvised sacred music is not falling into the pitfall of egoic

"self"-expression because it is turning the listener to the Divine,

rather than to the performer or to the form of the music. Someone being

musically expressive or improvising in an egoless fashion, while turned to the

Divine, is not a blank slate. Rather, he or she is creating in accord with the

aesthetics of Reality Itself, and is doing so in full relationship with any other

musicians improvising with them. Here is one of the most succinct summaries Adi

Da has ever given of the aesthetics of sacred, ego-transcending art of

all kinds, including sacred music:

My

true devotees give living human form to the Indivisible Presence of Reality Itself

. . . My true devotees "create" according to the aesthetic logic of

Reality and Truth, and (thus) they turn all of their living into limitless relatedness

and true enjoyment. They constantly remove the effects of separative existence

and restore the inherent form of things. They engineer every kind of stability

and intrinsic beauty. They give living human form to My Avatarically Self-Transmitted

Divine Transcendental Spiritual Presence of Love-Bliss and Infinite Peace. Their

eye [or ear] is always on the integrity of inherent form, and not on egoically

fabricated (and, necessarily, false and exaggerated) notions of artifice. Their

sense of form is always integrated, stable and whole, and always in present-time,

rather than gesturing toward some "other" event. Avatar

Adi Da Samraj

"I Have Come To Found A Bright New Order of Global Humankind"

Part

25, The

Aletheon |

"Baba Da's Great Tradition Improvisation

Orchestra" was an experiment in improvisational devotional music directly

encouraged by Adi Da in the musicians who were playing for Him. As one of them

put it, "There was no plan except to play for our Beloved Guru in the great joy

of His Presence."

2.9.

Musical Settings for the Poetry, Literature, and Leelas of Adidam

Over

the years, Adi Da has written poetry, literature, and evocative sacred texts that

naturally lend themselves to musical composition and innovation. Crazy

Da Must Sing — This

book of Adi Da's poetry was published in 1982, and devotee musicians have

been setting its poems to music ever since.

| | |

|

I

am as one — Adi Da's poem, "I am as one who left his home to do

a thing for man", set to music by Ray

Lynch. Sung by Crane

Kirkbride, on his album, An

Infinite Well. I

am as one — Adi Da's poem, "I am as one who left his home to do

a thing for man", set to music by Ray

Lynch. Sung by Crane

Kirkbride, on his album, An

Infinite Well.

|

| | |

|

My loved one sits upon my knee — Adi Da's poem, "My loved one sits upon my knee", set to music and sung by Pauline Chew, on her album, Songs for Baba Da. . . and the World. My loved one sits upon my knee — Adi Da's poem, "My loved one sits upon my knee", set to music and sung by Pauline Chew, on her album, Songs for Baba Da. . . and the World.

|

| | |

| | other

examples — "Mornings, No", "Forehead, Breath, and Smile",

and "When Things Have Left Him" from Eyes

In Other Worlds; "Ive Grown Used To Miracles" and "I Am As

One Who Left His Home" from the album, A

World More Light. |  The

Mummery Book — The Mummery Book

(Book One of Adi Da's Orpheum trilogy) is a sacred theatrical enactment

that combines acting, images, and music. Much music has been written for The

Mummery Book over the years, often completely new with each year's performance.

Here is just a small sample, composed and sung by Chris

Tong for Adi Da at the 1995 performance of The

Mummery Book on Naitauba, Fiji. The

Mummery Book — The Mummery Book

(Book One of Adi Da's Orpheum trilogy) is a sacred theatrical enactment

that combines acting, images, and music. Much music has been written for The

Mummery Book over the years, often completely new with each year's performance.

Here is just a small sample, composed and sung by Chris

Tong for Adi Da at the 1995 performance of The

Mummery Book on Naitauba, Fiji.

Leelas — The world's religious traditions

are full of religious stories being set to music: from Christmas carols, to Passions (e.g., Matthew's Passion), Easter hymns, and Pesach music in the West, to the tradition of Harikata in the East: a form of Hindu religious discourse in which the storyteller explores a religious theme, usually the life of a saint or a story from a religious epic using

stories, poetry, music, drama, dance, and philosophy. Adi Da has also

recommended that the leelas of Adidam be set to music and dramatized (particularly

for instructing children being raised in the culture of Adidam):

It's

the application of the arts, sacred theater and so on to communication of leelas

and instructional texts. And it should be done on a regular basis in all the regions.

. . Plus, there are other texts to be recited or dramatized, sometimes put to

some kind of musical setting for the recitation, or the words themselves chanted

or recited in a kind of musical manner. Leelas dramatized. The arts have got to

be brought to these matters for children and adults, a regular part of the sacred

domain. Avatar Adi Da Samraj, April 14, 2005 |

2.10.

More Examples of Adidam Music

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Ray:

My relationship with Adi Da Samraj over more than

25 years has only confirmed His Realization and

the Truth of His impeccable Teaching. He is much

more than simply an inspiration for my music,

but is really a living demonstration that perfect

transcendence is actually possible. This is both

a great relief and a great challenge. Ray:

My relationship with Adi Da Samraj over more than

25 years has only confirmed His Realization and

the Truth of His impeccable Teaching. He is much

more than simply an inspiration for my music,

but is really a living demonstration that perfect

transcendence is actually possible. This is both

a great relief and a great challenge.

|

| |

|

|

|

Ray sings with Adi Da

(1975)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

Crane and Adi Da singing "I Am

Who You Are" (1992)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Naitauba,

Naitauba Naitauba,

Naitauba

Composed by Jeff Hughes, played and

sung by Alexandra Fry, singing about the Spiritual

purpose of the island of Naitauba. (The words of the

song are "in Adi Da's voice" — in

other words, they are written as though He Himself

is speaking about Naitauba, but He never actually

spoke these particular words.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Many talented and creative musicians have created the full

body of devotional music in Adidam to date.[2] Only some

have been mentioned or represented in the above examples.

2.11.

Sacred Offerings and Chanting Occasions In addition to music

created specifically for the devotional context of Adidam, many traditional pieces

(Western and Eastern) have been performed for Adi Da in the context of a Sacred

Offering. This was a specific way through which devotees with musical talents

could deepen their relationship with their Spiritual Master, in person. Sacred

Offerings continue after Adi Da's human lifetime, offered by devotees to Adi Da's

eternally accessible Divine Presence.

All devotees, musicians and non-musicians alike, have been able

to express their devotion through music by participating in chanting

occasions where they sang to Adi Da, as in the occasion in the video

below on June 29, 2005, at The Mountain Of Attention Sanctuary.

2.12. Music as Sacred

Art and Means for Growing in the Relationship to Adi Da

| Devotees

in Washington, DC chanting to Adi Da |

| I play music all the time. I just use someone

else's hands.

Avatar Adi Da Samraj

In the Ruchira Avatara Gita not

every word or line of it is supposed to be the Guru Himself speaking; it's the

voice of the devotee. But the devotee is able to sing rightly about the Guru,

having been inspired by the Guru, so that the Guru in effect is singing the devotee.

Avatar Adi Da Samraj, April 27, 2005 |

All

devotees are called to take up one or more sacred arts, as an integral part of

their practice of the Way of Adidam. Unlike "conventional art", sacred

art is precisely not "self-expression": projecting the contents

of one's ego (generally, one's unconscious) onto canvas if one is a painter, onto

sheet music if one is a musical composer, or into one's singing if one is a singer.

Before all art started being reduced to self-expression in

the last few centuries, there was a shared notion (still intuited by many) that

the best state for an artist to be in was to be "inspired" (a word which

shares a common root with "spirit"), or "possessed" by a Force or Presence

greater than oneself, and to allow one's art to flow from that possession or inspiration. (Done right, one's "Muse" is the source of one's music. "Music" literally means "the art of the Muses".) That

traditional viewpoint is shared by Adidam, and "taken to the limit", in the sense

that the "Force or Presence greater than oneself" is the Very Divine. In Adidam, sacred art

has two aspects: - Its end or purpose is to transport

the viewer (if art) or listener (if music) into the Divine Domain, or at least

help them intuit or connect with It.

- Its means is the artist (if art) or the composer and performers (if music) becoming instruments of the Divine (through contemplation of Adi Da).

In this sense, practicing one's sacred art as a devotee of Adi Da is not different

from what all devotees are called to do as they grow in the practice of Adidam

altogether: to become instrumentality for Adi Da's Spiritual

Transmission where the means is surrender to the Divine, and the end (from

the Divine Viewpoint) is to magnify the Divine Transmission for the sake of the

Divine Enlightenment of all beings.

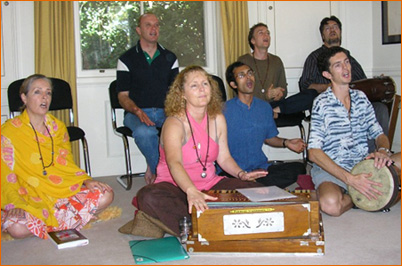

| Devotees

in Melbourne, Australia chanting to Adi Da |

Many

artists, creative people, spiritual Realizers, spiritual seekers, and social activists,

resonate with this notion of becoming instrumentality of giving oneself over

to something greater than oneself, for a higher purpose than self-fulfillment:

Lord,

make me an instrument of Your peace. St. Francis of Assisi |  |

As

practitioners of the Way of Adidam, we are called to give ourselves over through

our sacred art and through our practice altogether to the very Divine, to serve

the Ultimate Purpose of the Divine Enlightenment of all beings, through our becoming

instrumentality for the Divine.

To grow in one's sacred art certainly involves becoming

more proficient in all the technical dimensions of that art. If

one's sacred art is chanting, certainly singing off key does not

help the listeners connect with the Divine![5]

In general, lack of proficiency draws everyone's attention to the

deficiency rather than to the Divine. This applies to the chanter's

(or musician's) own attention as well. If one is not highly proficient

technically, then much of one's attention will be going toward "getting

it right", and there will be that much less free attention

to devote to the Divine.

| Antonina

Randazzo leading a chanting seminar in New Zealand |

But

growing in one's sacred art is only secondarily a matter of technical mastery.

Primarily, it coincides with growth in one's devotional practice and one's ability

to invoke Adi Da as the Divine. The key then is to have enough free energy and

attention to invoke Adi Da, so that one is practicing one's art in the self-forgetting,

Him-remembering disposition.

It

is important to understand that the matter of sacred art is a profound discipline.

In the conventional setting, to be an artist, you must be technically competent

and creatively enthusiastic. In the sacred context, though, you must also, at

the very least, be someone who is really doing sadhana and be active from the

real depth of devotional Contemplation. In sacred art, you are required to press

beyond your usual tendencies, what you are assuming yourself to be all the time,

and all of your presumed limitations . . . The doing of sacred art requires not

only full capability and competence relative to the technicalities of the art

and real creativity of course, but the performance of sacred art requires the

fullest development of sadhana and submission to the Divine.

Avatar Adi Da Samraj

You

have to understand that sacred music is not a performance. It is not about how

good you can do it. It is a sadhana. Chanting and sacred offerings occasions are

not for the individuals who are actually making the vocal [or other musical] offering:

these occasions are for everyone else there as well. The person making the offering

has to be very sensitive to the fact that it is his or her function to make a

devotional offering and pull everyone into making that offering to Me. The offering

and chant being done have to effectively do that, so that everyone is participating.

Really, the person making the offering becomes invisible. . . . These offerings

are participatory occasions in devotion to Me. Avatar Adi

Da Samraj, May 2, 1992

It is presumed that those participating [in a Sacred Music Offering] will be entering into Divine ecstasy. That is the whole purpose of the music, to serve the ecstasy of all present.

Avatar Adi Da Samraj

|

When performing music is our sacred art, we

not only master a musical instrument; we also allow the Divine to master our body-mind,

and transform it into an instrument that the Divine can play.

| Devotees

in Adi Da Samrajashram chanting to Adi Da |

On

the Celebration of Adi Da's Jayanthi [birthday] in 1993, devotees were invited

to a sacred performance offered to Adi Da by the music guild at Adi Da Samrajashram.

Before the musicians began to play their instruments, Adi Da inspired them with

instruction relative to sacred art and its traditional origins:

For

those of you who are going to celebrate the sadhana of music here tonight, do

so in this spirit. Do it as a means of ecstasy, not self-conscious, full of thought,

but as devotion to Me, beyond thought, to become ecstatic and to serve all your

fellow devotees here in their ecstasy, their movement beyond themselves. Do not

allow it to be a concert with boring middle-class people watching or listening,

while you, as boring middle-class people, sing or make music, sounds of one kind

or another, and everybody contributes another $50 to the Ladies Music Society

at the end, you see! Do not let it be that. Make it more like what in the Sufi

tradition of Islam is called "Qawwali". Those who perform music

in the Qawwali tradition observe all those participating. It is presumed that

those participating, just sitting while others play and sing and so on, wiill

be entering into Divine ecstasy. That is the whole point, that is why they do

the music, but they observe everyone present. If someone enters into ecstasy during

a particular passage in the music, in the song, with the instruments or whatever,

the musicians observe the discipline of continuing with that until the person

comes out of it. If they are somehow the cause of that ecstasy, they must serve

it until the person returns to a more normal attitude. So the musicians are there

to serve the ecstasy of all present, and they observe the discipline of observing

[the participants] to serve in that process, and will not leave them, will not

break off, saying, "Well, we have had five minutes of music and that's the

end of it." No, they just go on and on until everybody who has gone into

the fullest ecstasy has done so and come back and resumed their normality. You

Westerners have this concert mentality, egos getting up to be praised for their

performance. Music, from the traditional point of view, is only for ecstasy,

only for self-transcendence in Divine Communion. Music is a means for it in the

context of the whole culture of Divine Communion, which everybody knows about

and is practicing as well. But that is the point, that is what they are there

to serve. They will not interrupt it or stop it as long as people are in that

ecstasy. So they do not do "concerts" in the sacred traditions.

They do not expect praise. They are not there as egos expecting to be honored

and so forth. Honors are given, of course, but that is not the point. The point

is God-Communion. That is the traditional point of view of the arts. And they

are there to serve that in everyone and through these unique means, which are

part of the collective culture which adds something to the daily practice of every

individual, provides occasions of this unique means of Divine Communion. It is

not ego games, it is not a mere concert, it is not a civilized performance. It

is just to enhance what everyone is struggling to do every moment, which is to

enter into most direct Communion with the Divine and lose egoic self in order

to do so. You are here to serve My devotees, their Communion with Me, their

going beyond themselves. Be sensitive to them in the process. You, yourselves,

enter into it without self-consciousness. The notes are not the point. They are

not an end in themselves, they are strictly, or only, means. You are not here

to be praised or accepted, you are here to serve My devotees in My Company, to

ecstatically be in My Company through this unique service at this moment. Avatar

Adi Da Samraj, November 3, 1993 |

So in addition to technical

mastery of voice or musical instruments, and in addition to one's personal expression

of devotion through the music, the sacred musical performer must also become adept

at using his or her craft to help draw out the devotional participation of everyone

else in the room:

In

a secular situation, the focus is on the performance and on the ego. In the sacred

situation, the focus is on the Divine, on the Realizer. The Realizer or the Divine

is the subject of devotion. Therefore, this requires self-transcendence, not self-presentation.

This is the most difficult aspect of the art to learn and it requires maturing

in the process. These offerings are participatory occasions in devotion to Me.

Part of the training is to be able to perform in these sacred occasions and this

requires great skill in order to provoke participation on the part of everyone.

These occasions are not just for the person making the devotional offering to

express his or her own devotion. Avatar Adi Da Samraj |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Singing

Opera with Adi Da

During His years of face-to-face

Teaching Work, Bhagavan Adi Da used singing opera

with His devotees as a skillful means that drew those

present into selfless feeling-ecstasy. Longtime devotees

Aniello Panico and Roger Ohlsen describe what that

was like.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

I

Realized That I Was "Playing for God" In the

early 1980s, Bill Somers had already realized what

he had held to be his life's ambition: to be principal

clarinetist in a symphony orchestra. But this accomplishment

was not enough for Bill, after all; his heart was

not satisfied. And that was a good place to be! It

led him to his Spiritual Master.

Bill

Playing "Interlude" Bill

Playing "Interlude"

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

"This

is the God for me!" In this radio interview

(with Aaron Joy), rock musician Theo Cedar Jones describes

how he became Adi Da's devotee; how Adi Da transformed

his entire manner of singing and his craft of songwriting;

and the creative challenge of communicating Adi Da's

Presence and Teaching through the medium of rock.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3. Participate

in a Sacred Musical Occasion

Enjoy over an hour of the devotional music of Adidam

— you can listen to most of the examples presented above in our Music Player

below.

We have organized it as a Sacred Occasion. First, while you are

settling into your seat, Baba Da's Great Tradition Improvisation Fusion Orchestra

plays some transitional music to help transport you into the Sacred context. Then

Antonina Randazzo provides a formal Invocation of Adi Da. All the subsequent pieces

continue to magnify that Invocation, reflecting in many ways upon Who and What

Adi Da Is — the Wonder, the Blessing-Power, and the Happiness of the Divine

appearing in the world in human form — as well as the nature of egoity ("May

Your Radiant 'Bright' Blessings Awaken me, whose eyes are covered over by the

images of a separate self") and of Reality Itself. On the more lively tracks,

feel free to get out of your seat and "Dance

Down The Light"! The Sacred Occasion closes in the way devotees of

Adi Da often close their weekly Guruvara occasions: with the singing of Gurudeva Hamaaraa

Pyaaraa ("To Our Beloved Guru"), and closing with the recitation of the Sat-Guru-Naama Mantra. For those tracks that

have associated albums, you can click the album cover to find out more about the

album.

FOOTNOTES

|

One

of [Adi Da's] great missions relative to human civilization is to restore the

deep purpose of art art in all forms: visual art, literary art, musical art,

architecture all of that can be made to support the life of resort to the Divine,

the life of Communion with the Divine. . . . He has encouraged all of His devotees

to create beautiful environments, to create beautiful music, to create beautiful

artistic works.

One

of [Adi Da's] great missions relative to human civilization is to restore the

deep purpose of art art in all forms: visual art, literary art, musical art,

architecture all of that can be made to support the life of resort to the Divine,

the life of Communion with the Divine. . . . He has encouraged all of His devotees

to create beautiful environments, to create beautiful music, to create beautiful

artistic works. Music

works upon our nervous system, our feeling of life, and creates a symphony out

of our emotion. In other words, a summary of feeling is somehow gestured out of

us through the impact of music, whereas a note-by-note analysis of it would have

no meaning. You cannot somehow find out how music has that emotional effect. It

is more magical, more arbitrary, more free than that. It is not discursive and it is not picture-making. Music undermines your effort to make a picture. It also undermines your effort to make sense, to make meaning and order out of it. So you are left with what it is all reduced to when meaning and pictures are not your capacity. You are left with this emotional impact that seems profound and beautiful, but it is not reducible to meaning. It is reduced to the feeling that you cannot put on the page.

Music

works upon our nervous system, our feeling of life, and creates a symphony out

of our emotion. In other words, a summary of feeling is somehow gestured out of

us through the impact of music, whereas a note-by-note analysis of it would have

no meaning. You cannot somehow find out how music has that emotional effect. It

is more magical, more arbitrary, more free than that. It is not discursive and it is not picture-making. Music undermines your effort to make a picture. It also undermines your effort to make sense, to make meaning and order out of it. So you are left with what it is all reduced to when meaning and pictures are not your capacity. You are left with this emotional impact that seems profound and beautiful, but it is not reducible to meaning. It is reduced to the feeling that you cannot put on the page.

Devotional

invocation

Devotional

invocation Om

Sri Da (excerpt)

Om

Sri Da (excerpt)

Ruchira

Avatara Gita (The Avataric Way Of The Divine Heart-Master)

Ruchira

Avatara Gita (The Avataric Way Of The Divine Heart-Master) Danavira

— In the experimental Adidam album, Danavira (The Hero

Of Giving), professional jazz composer,

Danavira

— In the experimental Adidam album, Danavira (The Hero

Of Giving), professional jazz composer,

Baba

Da's Great Tradition Improvisation Fusion Orchestra

Baba

Da's Great Tradition Improvisation Fusion Orchestra