|

7. The Artfulness of Helping Each Other

|

You are supposed to be making Good Company for one another. That is why the Reality-Way of Adidam is a culture of "radical" devotion to Me, a culture of Samadhi — because it is this disposition that you must serve in one another, rather than reinforce body-identification, or "organism"-identification, in one another. You must reinforce the sublime disposition of ego-surrendering, ego-forgetting, and ego-transcending devotional Communion with Me — rather than reinforce the disposition of body-identification in the egoic sense, and stress that presumption.

Avatar Adi Da Samraj, Notice This |

A gathering of people who are under vow saying they do recognize Me must be guided. That's what they are consenting to be, under guidance, under authority, constantly instructed, constantly corrected and obliged. That's what it means to be under vow. But if you don't give people that guidance, but instead, are always kissing them on the cheek and patting them on the head and scratching their backs, you are betraying their vow. Beginners who take that vow are from that moment under the obligation of guidance. Then if you look to the slightest right or left, you're supposed to get a no-nonsense correction, be constantly directed. Avatar Adi Da Samraj, Spoken Communications, July 29, 2008 |

While we could write an entire book about both the maturity and the art involved in being an Adidam cultural server of one kind or another, in this article, we will just mention a few points in passing, to give you a sense for the issues involved.

The Virtues of a Well-Functioning Culture of Devotees in Helping One Take Up Disciplines

When the Adidam culture is functioning as Adi Da intended it, it has many advantages over you trying to take up disciplines on your own. Here are just a few:

-

Group discipline — It's so much easier to adapt to a discipline — say, the raw diet — if you are living in a household with other devotees, and everyone else is already adapted to the raw diet.

devotees eating raw together

Similarly, it's easier to get up at 5am every morning to meditate, if everyone else in your household is getting up too (and particularly if someone is walking throughout the house ringing a bell softly at 4:45am!). Such a "cooperative community" circumstance more or less automatically provides the three key elements of a well-functioning Adidam culture: form, inspiration, and expectation.

-

Advice from experienced practitioners — You're a newbie with some discipline, but you can get lots of excellent advice from devotees who have been around longer, especially those have already adapted to the discipline.

-

Mirrors of self — It generally is easier for others to see us than for us to see ourselves. That's one of the primary purposes of "devotional groups" in Adidam: everyone knows everyone else in the group, and others can help you identify egoic "loopholes" you haven't yet covered with disciplines. Also, your fellow group members can point out if you're slacking off, cutting corners, etc. on a discipline you had previously agreed to take on. For much more on this, listen to Adi Da's instructions in His 1993 talk, "When the Tiger Disappears":

Problems That Can Arise When Poorly Trained Devotees Try to "Help" Each Other Take Up (and Persist In) Disciplines

Eventually those of us practicing the Way of Adidam will develop comprehensive education and training in every area, not only for devotees trying to take up various disciplines, but for cultural servers (or devotees in general) trying to help others take up new disciplines. But in the meantime, we'll just mention a couple of major pitfalls to avoid (if you are a helper) or to watch out for (if you are being helped).

-

Cultural servers with "control numbers" — In part 5 (Disciplining Not Only the Self-Indulger but the Self-Discipliner), we mentioned how Adi Da identified various styles of egoity: those characters who tend to indulge themselves a lot; and those characters whose style of egoity is idealism, coupled with self-control and control of others. In some sense not surprisingly, the latter type tend to gravitate toward being cultural servers, since it fits that style of egoity so well. And there's where the problem lies: someone with that style of egoity can end up just playing out their "control numbers" on other devotees. Such a devotee will not be very good help for someone tending toward self-indulgence. Control numbers in the form of nagging, threatening, humiliating, shaming, acting superior, being righteous, etc. not only don't help, but they tend to trigger an oedipal reaction in the person on the receiving end — then the person not only has their existing difficulty with adapting to the discipline; they now have their reaction to this kind of "help" that now wants to continue indulging just to get back at the jerk!

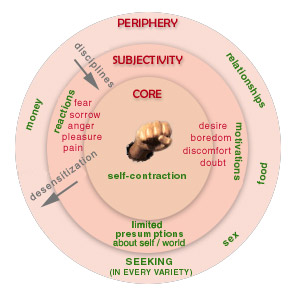

Now it is true that, eventually, as we grow in the Way of Adidam, we reach a point where we are disciplining even such oedipal reactions in ourselves — which is fantastic, because then anybody can help us, even if they're an asshole! We are able to receive the message, without shooting the messenger. But such capability (to be responsible for transcending oedipal reactions) is only developed at level 1.2 in the Way of Adidam — long after all the basic disciplines are supposed to be in place. (The diagram below illustrates how the "periphery" of the ego — with all its very obvious dramatizing in the areas of money, food, sex, etc. — must be disciplined first, before one takes on the deeper "subjectivity" level, which includes all the oedipal reactions.)

So we really need those who are helping us with the basic disciplines to not being indulging in their control numbers or other oedipal patterns, as they "help" us.

-

Dysfunctional "devotional groups" filled with case talk — In His 1993 talk, "When the Tiger Disappears", Adi Da makes clear that a rightly functioning devotional group is to be about constantly identifying parts of each group member's "egoic patterning" that have not yet been covered by disciplines, and having the group member take on new disciplines ("yamas" and "niyamas") even every week (if they can sustain that pace). However, what often happens instead, is that no new disciplines are taken on by anybody, and the entire time of the devotional group is spent indulging in what Adi Da calls "case talk": group members talking endlessly (and generally problematically) about their egoity, but without taking on any disciplines to address it. The end result is not only a group that didn't fulfill its purpose, but a meeting that ends with everybody feeling completely drained by having to listen to everybody else's problems (as well as their own)! This is an example of how devotees can end up being "bad company" for each other, rather than "good company". As Adi Da puts it:

You can waste those opportunities of gathering together. Especially if you don't apply new disciplines. . . . If you're not working at it, it's boring. You're just falling back into the "soup" again, and getting dull and repetitive, preoccupied with trivia and the perpetuation of your bondage. To embrace this practice in My Company requires the willingness to work, to do sadhana [spiritual practice], to deal with yourself, to embrace discipline, to abandon habits, to adapt to principles of right living, to curb what needs to be managed so that you can observe further.

And you serve one another. By personally practicing, you bring clarity to those groups. Therefore you have the clarity not only relative to dealing with yourself, you have the clarity to address others, to observe them, to see the detail that they might not be quite catching, to require more of them. This is how you serve one another. Otherwise you make your so-called "reality consideration" into a social occasion merely. . .

A new agreement, a new discipline, made known to others, and you to be held accountable for it by others, especially those in the group that you meet with regularly, and others who are intimate with you, perhaps. So that's work. And that's interesting too! Instead of just getting together and babbling in some superficial, social manner, this is the business. . . . And not be dragging everybody down into the "well" of dramatizations, requiring the culture, then, to be basically some sort of a nursing place, to struggle with people in the midst of their dramatizations. . . . Your reactivity is your concern. Nobody should have to suffer it. No one. This life sign is very brief. Make it precious, then. Honor it, by right life.

Avatar Adi Da Samraj, When the Tiger Disappears

-

Cultural servers recommending disciplines on the basis of what they don't like about a person — As you can see, Adi Da recommends that the culture not allow devotees to simply dramatize their "stuff" to each other. The culture of Adidam is intended for humanly mature adults who are able to make (and abide by) such agreements with other, for the sake of everyone's equanimity and depth of practice. Someone who is constantly dramatizing dis-serves everybody's practice.

On the other hand, sometimes cultural servers (or other members of one's devotional group) will take this principle too far, and recommend for a person a discipline primarily on the basis of something the person does that the server is personally "bugged by". But that is not the appropriate basis for recommending a discipline for a person.

The primary guideline for choosing (or recommending) disciplines for a particular person is on the basis of noticing what causes them to lapse from the (moment-to-moment) practice of "radical" devotion; creating a discipline for whatever is distracting their attention, feeling, etc. helps return the person to "radical" devotion. So that should be the rationale behind recommending a discipline, not "everything I don't like about Joe". Indeed, the things that bug a cultural server about Joe are probably causing the cultural server himself (or herself) to lapse from "radical" devotion — and are a good basis for a new discipline for the cultural server, to serve his or her practice!

Generally, not being judgmental is a good disposition for cultural servers to have relative to the devotees they serve. One can never know who may suddenly begin to grow in practice. As Adi Da reminds us:

None of you should feel disqualified, in principle. None of you should feel peripheral.You are all My devotees, here to manifest your fullest capability as My devotee. How do you know who will be exemplary? Do not make social measures of the practice of others, on the basis of the fact that they are apparently modest, for example, or that they are characteristically peripheral by choice or tendency. You are only free, but obliged to manifest your greatest sign in My Company, and in the company of others. The humblest of My devotees are the greatest of My devotees. Those who relinquish the ego are the greatest.

Avatar Adi Da Samraj

-

A "religious" misinterpretation of disciplines — Many religious traditions have a set of behavioral prescriptions. (The Ten Commandments of the Judeo-Christian tradition is an example most readers are familiar with.) These prescriptions are associated with morality: one is a "good" Christian (or not) depending on whether one conforms one's behavior to these behavioral "laws". In the more "traditional" segments of a religious population (for example, Orthodox Judaism, fundamentalist Christianity, or Sharia-based Islam), there can sometimes be an intensely moral context in which one is rewarded by one's peers for "good" behavior; and one is ostracized — or even shamed, humiliated, or punished — for "bad" behavior. Almost all of us have some personal knowledge or experience of this (each of us to different degrees, depending on our background).

But none of this has anything to do with the "right life" disciplines of Adidam, or how devotees can best serve each other in taking up these disciplines. The Way of Adidam is not based on "heaven" and "hell", where being a "good devotee" gets you into heaven, and the "right life" disciplines define who is a "good" devotee (and who is not).

The culture of Adidam is about growth in practice in the Way of Adidam. And growth in the Way of Adidam is entirely about personal responsibility. While it is not advocated, you always do have the option of taking forever to adapt to the "right life" disciplines. . . but you will then also take forever to Realize the Divine (and you will suffer the endless round of pleasure and pain, births and deaths, gains and losses, etc. in the meantime). But you know the tradeoffs and it's finally a matter of your own personal choice.

Other devotees can encourage you and inspire you on the basis of their love for you, their seeing how you are suffering because you are doing X, and they can see how your suffering would be alleviated if you took on a discipline regarding X, etc. But there is no righteousness on their part about all this. There is no "Joe is a 'bad' devotee because he never can get his act together in this area". It's always our compassion guiding our serving Joe, and it is always Joe's personal choice in the end.

The most effective Adidam cultural servers understand all this, and don't bring righteousness or judgmentalism into their service to others. The culture of Adidam is all about encouraging and inspiring personal responsibility. It is also about expecting personal responsibility from someone, once someone has made an agreement to be accountable do something (for example, in one's devotional group). But there can be no cultural expectation until each person chooses to be accountable; such choices can never be coerced.

-

Insensitivity to (or ignorance of) the actual human (and even cognitive) process involved in taking up and adapting to a new discipline. When someone fails to enact a new discipline, some of us (trying to "help") tend to automatically respond by giving them a lengthy "sermon" about why the discipline is a good thing, why not doing the discipline is bad, etc. This response presumes that the reason the person didn't do the discipline in that moment is either a disagreement with (or a lack of understanding of) the rationale behind it; or an unwillingness to take on the new discipline.

But often the actual reason is much simpler. One of the basic cognitive realities in habit formation is that, even when one completely understands the virtue for engaging a new discipline and is not resisting taking it up, one simply will forget what one is supposed to do, and automatically engage one's old behavior instead. That's part of what is meant by "force of habit".

When forgetting is the reason a person has "erred", the best response on the part of a cultural server is a simple reminder: "Remember to do X" or "Did you forget to do X?" — this instead of giving the person a lengthy sermon (which would surely rub them the wrong way).

Forgetting is a very common (and natural) aspect of forming a new habit (especially when one has been engaged in a different behavior for years). Indeed, in the beginning of forming a new habit, it is very common for one to remember one's intention only after one has automatically engaged in the old habit — one slaps one's forehead, and says "Oh, crap — forgot again!". It is not at all uncommon to do this for tens (or even hundreds) of times, before one reaches the point where one remembers one's new intention before acting, rather than after. In the logic of habit formation, that's a moment for celebrating! And then persisting in the new habit, all the days after.

| Quotations

from and/or photographs of Avatar Adi Da Samraj used by permission of the copyright

owner: © Copyrighted materials used with the permission of The Avataric Samrajya of Adidam Pty Ltd, as trustee for The Avataric Samrajya of Adidam. All rights reserved. None of these materials may be disseminated or otherwise used for any non-personal purpose without the prior agreement of the copyright owner. ADIDAM is a trademark of The Avataric Samrajya of Adidam Pty Ltd, as Trustee for the Avataric Samrajya of Adidam. Technical problems with our site? Let our webmaster know. |