|

“Tacit

Glimpses”: |

|

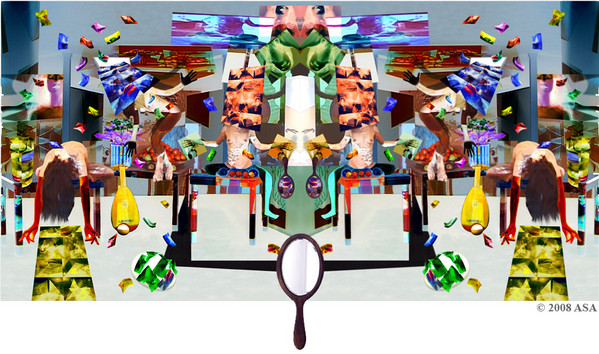

| The Pastimes of Narcissus

I, 2006 (from Spectra One) |

“The image,” writes Adi Da, describing the making of his own art, “is the response itself — ecstatic, beyond and prior to ‘point of view’, ‘object’, separateness, duality, reflection, and likeness.” It is rare that artists have the courage to stand for a pure view of art. Yet in his two recent collections of essays on aesthetics, “Transcendental Realism” and “Aesthetic Ecstasy”, Adi Da Samraj raises the flag for an authentic spiritual experience embodied in art by calling for a “true art” that yields an immediate, sensory experience of a world of energies that transcend human perspectives and attachments. For him, the apparent multiplicity of ordinary events and images can be transformed by the creative artist into an experience of aesthetic ecstasy and inherent unity. Both manifesto and meditation, these pieces are intended to not only open our perception to a more fully present experience of art, but to allow Adi-Da’s own image-art to effect this change. Weaving intention and actuality in his writing, Adi Da’s “Transcendental Realism” and “Aesthetic Ecstasy” are challenging and rewarding reading for artists and anyone interested in art as a transformative experience.

Although his own spiritual realization unfolded spontaneously, Adi Da also makes use of his profound learning in philosophy, psychology, art, and the esoteric, psycho-physical traditions of both Asian and Western cultures. And he is aiming to do nothing less than restore transcendental purpose to post-modern culture. The text image appearing on the cover of both volumes — a triangle within a circle within a square, inscribed with the daisy-chained aphorism “Reality Itself Is Truth Itself Is The Beautiful Itself Is” — is a clear attempt to replace “the Good, the True, and the Beautiful” as the founding triad of Western high culture, while also establishing the three aforementioned shapes as the “primary geometries” (each bearing a unique esoteric meaning) upon which all art is based.

|

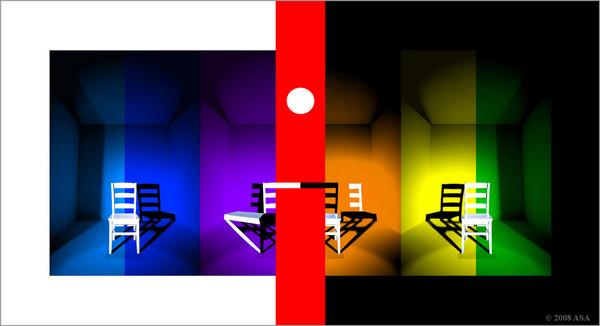

| The Pastimes of Narcissus

II/92, 2006 (from Spectra One) |

Adi Da asserts that true art has one and only aim: moving the viewer toward an ego-dissolving mystical experience of wholeness, opening us to a visual epiphany — a sensual state of immediacy and pure enjoyment. He builds his own art in many ways: initially working for some years with multiple exposures of photographs that capture, “in camera”, a multiplicity of viewpoints, he now works almost entirely with purely digital constructions. Some recent works have combined his visual strategy of multiple perspectives with mandala-like central geometry, presented on a scale so large as to encompass the viewer. Using the modernist technique of scale developed in the paintings of the ‘70s and ‘80s, the works also incorporate saturated color and an isolation of the image in a darkened space, giving the images a sense of power. Adi Da intends the contradictions within the image to inspire a vivid state of awareness that transcends causal thinking. These visual images oscillate with contemplation, echoing modern poetry’s repetition of images and use of multiple voices, undermining, as Adi Da writes, a fixed perspective.

|

My image-art can be characterized as paradoxical space that undermines ‘point of view’. That undermining (which occurs in any instant of fully felt participation in any of the images I make and show) allows for a tacit glimpse, or intuitive sense, of the Transcendental Condition of Reality . . . totally beyond and prior to “point of view”. |

As a young man Adi Da studied Gertrude Stein, and, as much as I avoid the biographical view, he has distilled her essence in image-repetitions that ultimately dissolve any fixed notion of what we are seeing. A context for Adi Da’s visual aesthetic can also be found in Kazimir Malevich’s purity of geometric form, Kandinsky’s harmonic improvisations, and Picasso’s and Braque’s Cubist investigations of multidimensional space; similarly, these artists wrote compellingly about their visions. Artistically aligned with the basic strategies of modernism, in his writing Adi Da calls for a “new-old” kind of “Conscious Light”.

|

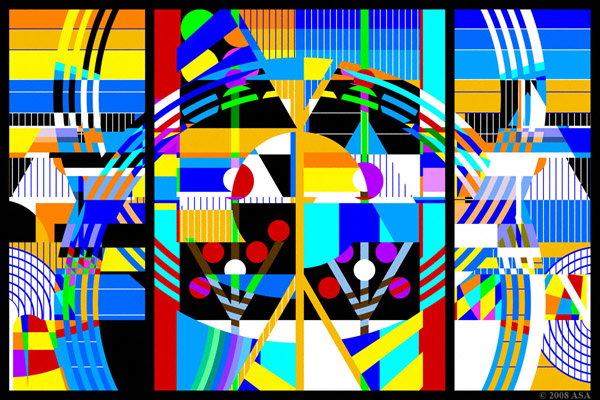

| The “First Room” Trilogy

I, 2006 (from Spectra Ten) |

Adi Da’s writings, though they arise from his own direct spiritual experience, seem nonetheless informed by Asian spirituality, Western Platonic notions of art, and echoes of cognitive, perceptive and psychological theory. Still, the writing is as much poetry as a meditation on the fundamental nature of art, and understanding it will depend on your ability to allow his words to encompass specific and multiple meanings. Adi Da’s aesthetic philosophy compresses language in a style that many will find demanding, but readers will find these essays well worth the effort. This compressed ‘morse code’ becomes a leitmotif of the writings, recalling the meditations of the young Giorgio de Chirico, whose illuminated experiences provided the impulse for his enigmatic paintings. Indeed, while Adi Da’s aphorisms run parallel to the kind of thinking expressed by artists for whom perceptions appear intuitively, we also find in them reflections arising from an expansive inquiry into art and spiritual experience. Both publications include a glossary that introduces you to basic elements of the artist’s philosophy. Perhaps the best entry point comes with the essays collected in “Aesthetic Ecstasy”, a critique of the art world written in language more familiar to a general audience.

I found Adi Da’s rejection of the art market’s commodity a welcome criticism of the superficiality and abstruse discourse currently dominating the art scene. Ironically, in Canada, where I live, artists are workers in the “cultural industries” — an essentially socialist idea that nonetheless bases itself on economics, changing the role and perception of the artist from café-society slouch to that of a “cultural worker”. Commodity, developed through the system of galleries, museums, art fairs, and granting systems, has become a kind of inescapable black hole for art. Taking apart the art world’s conventions, Adi Da argues convincingly for art to become instead the means for an authentic transformative experience. Living far from the centers of commerce, he has a detachment that allows an understanding of the system, and the spiritual conviction to make his ideas known. Artists who deeply feel the sensual and spiritual energy of creativity will undoubtedly embrace his view.

Adi Da’s incisive critique of contemporary art’s cleverness and superficiality lays bare a reality many recognize but are too intimidated to express. With his pointed description of the media-driven mindset employed by museums, Adi Da shows how these institutions have come to dictate how we should feel and what we should think about art. His wit cunningly uncovers issues many artists choose to ignore. While some curators object to these psychological controls, it is, as Adi Da points out, mainly in the art world where art becomes intellectualized. Tellingly, he compares this to the gut feeling and direct emotion that modern music still manages to evoke in contemporary audiences, leading us to wonder what forces the creative spirit into the cynical circuit of art world accounting.

Adi Da’s notion of “image-art” — the perceptual threshold where art merges surface and symbol — is liberating for artist and audience alike. Although evocative, images, like feelings, are unquantifiable. Freeing his “participant” to experience the poetry of images without conceptual definition, Adi Da rejects contemporary culture’s love of surface, its dependence on representational narrative. For Adi Da, art has the potential to illuminate consciousness — to give form to the “aesthetic ecstasy” of engagement. He writes,

|

My image-art functions entirely in the context of perceptually based whole bodily (or total psycho-physical) participation. My image-art has no political purpose or function. My image-art does not, itself (or by intention), represent any system of academic comparisons and historical accounting. . . My image-art is the “subjective” space of participation for whoever participates in it. |

Adi Da proposes that the expression of feeling in form allows a boundary-less aesthetic — an unmediated engagement with the participant. It is an idea of image-art that will no doubt be welcomed by many artists who strive to make images but who feel caught in the tension between consumerism and materialism.

Adi Da’s art eschews the Western development of linear perspective, as well as the more recent use of formalism, that turns the aesthetic experience itself into an art object. In his art, the world is a mutable place where no single viewpoint dominates. Both representational and formal streams have merit when handled by illuminated artists — from Vermeer to Rothko or Wang Wei — but, according to Adi Da, even representational art is too conventional to effect transformation. Moreover, our obsession with stylistic categories, he says, obstructs direct experience of art. True art, on the other hand, leads inevitably to “aesthetic ecstasy”. Adi Da’s challenging of conventional ideas can make for some dense reading, but its cumulative effect has force.

Expressions of intentionality have become increasingly common in the art world, but they are rarely made by those as thoughtful as Adi Da. His broad argument for transcendental realism over against the limitations of art history is strong stuff. While visual art does not always express the artist’s intention, good art should always do so, and it should do it forcefully. This divide separates the high-minded vogue for the artist’s statement from works that actually realize the artist’s vision.

In a literary sense, some may find the challenge of “Transcendental Realism” a large, rather rhetorically weighty argument for his work to sustain. It would certainly be interesting for other artists to engage with him in a dialogue, one that explores the essential vitality that is the peculiar domain of the true artist. Seeing Adi Da’s works themselves (catalog reproductions fail to do them justice) allows you an experience of the artist’s intention to create an experiential and transcendent image-art.

|

| Alberti’s Window I (detail),

2006–2007 (from Geome One) |

Adi Da’s image Spectra One I/1 (pictured in Transcendental Realism) brings up many themes — light, no “point of view”, centrality, and geometry; each are elements of his call for a new kind of art, and central to the aims of his own work. The suite Geome One: Alberti’s Window, illustrated in Transcendental Realism (see also above), contrasts Adi Da’s image-art with Renaissance illusionism. Viewing the piece, one becomes engaged with a geometric, discontinuous space that becomes a full contradiction of the fixed frame of reference — Alberti’s window — that forms the basis for much of Western art history. While this series is the most non-objective of his works, the Spectra Suites nonetheless employ elements of the visible world to create a realm of paradox. Visual art, like music, forms a harmonic structure through multiple shifting, ambiguous states of mind and layers of psychological and spatial perspectives. Adi Da often uses prismatic repetition — perhaps absorbed from his interest in modernism — creating a fluctuating perspective of multidimensional space. His intense use of color is brought to life through digital processes that allow for large-scale production of invented geometrics and ambiguous spaces:

|

My process of creating images brings together two principal elements, in a complex approach. One is the comprehensive element of form, and the other is the element of fundamental content (or essential meaning). On the one hand, I constantly exercise the formal element, and, thus and so (and by means of an always spontaneously free process of improvisation), I strictly control and order the structure of the images I invent. On the other hand, I am, likewise constantly, intent upon maintaining and profoundly enlarging the characteristic of meaning. Indeed, the meaning-content is always primary. |

Many artists have been stymied by the intellectual and economic machinery of the art world. It is an environment that negates the lyrical, the voice of the mystic, the sensuality that expresses the fragility of existence. In arguing for authenticity in art, Adi Da argues for those artists that cannot give voice to these feelings, either because they are hamstrung by the economics of the gallery system, or because they are stymied when faced with the smoke-screen rationales of the social and commercial sub-industries that feed off the artist. In this “fearful new world”, only the calculating and the lucky survive.

Most artists feel their work is something alive and irreducible, and they naturally want to protect it from classification. Images embody the spiritual expression of an artist’s work because their qualities cannot be reduced to formal analysis. Exploring this notion, Adi Da writes,

|

I am calling for a right and true use of the image-art I make and do — a use to which even all art should be put — in which the viewer is simply face to face with the art, without anything or anyone in-between, and with no extra-artistic uses whatsoever. Any true moment of participation in a work of art is — in the most positive sense of the word — ‘use-less’. . . there is only the moment in which the viewer fully participates. |

Such intentions can never be fully explained by historical influences or deconstructive tropes. They are the marks of an authenticity that, more than ever, the world is longing for.

Adi Da extends and expands an alternative understanding of art that has run like an underground stream through history: appearing intermittently in the meditations of the scholar-artists of China’s T’ang dynasty; in the writings of Leonardo and Michelangelo in the Renaissance; and in the aesthetic theories of Kandinsky and Mondrian in the modern era. Taken together, the writings of these artists reveal a long-neglected tradition of insight, one that has been rejected in our culture’s dismissal of anything that cannot be positively proven. These artists’ insights — however marginalized they have become in the history of knowledge — require a language capable of expressing the intrinsic qualities of art.

|

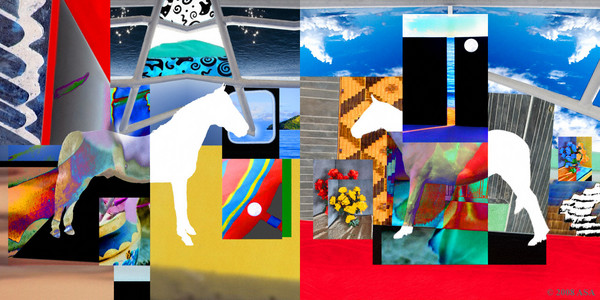

| A Horse Appears In The

Wild Is Always Already The Case, IV/1, 2006 (from Spectra Two) |

As art history formed in the nineteenth century, it took its modes of classification from archaeology, botany, and zoology. Thus formed, art history was never purposed to convey an experiential state of mind, even though such experiences were embedded in the artist’s touch. These illuminated writings did appear, but not in the realms of formalist Western art history. Instead, they were found, from the Renaissance forward, in poetry, music, in biography and art theory, in the disciplines of anthropology, history of religions, psychology, — all forms that explored human experience. Suzanne Langer, Titus Burckhardt, Mircea Eliade, James Hillman, and others investigated the experiential transformation of feeling into form, and essence into image. The modern artists’ manifesto became a call to arms for disrupting the conventional view of art.

This breaking with convention is precisely the aim of Adi Da’s book. Alongside his philosophical stance, he outlines the spiritual intention of his art, staking out new ground in this important alternative body of knowledge. Not only rejecting historicist notions of progress in art, Adi Da also transcends mere critique to assert the power of art to transform the viewer’s actual experiential state.

The root of this transcendent art, Adi Da writes, is the radiance of a world penetrated and informed by a divine light:

|

I have no impulse to make and do art on the basis of ‘post-modern’ (or even ‘post-civilization’) cultural breakdown. This is why I worked so intensively to re-establish a basis for Reality-culture, a Truth-culture — before I could intensively make and do art within the context of an actual and living culture of Reality and Truth. |

Before we can participate in truth and the beautiful as aesthetic experience, Adi Da says, our emerging world culture needs to be transformed by the possibilities of sacred energy, the Light that runs through all things. It is a mystical view that runs through both Western and Eastern cultures, from the biblical call to “see with new eyes”, to St. Francis Assisi’s understanding of the natural world as expressing divine presence, to the Chinese scholar-artists’ perception of the formlessness in form, to the transformative spaces of Monet or Rothko. This intuitive stance provides hope for romantic and mystical artists, hope that the essence of their work will become manifest.

That Adi Da challenges our culture to return art to its original, sacred purpose without merely recreating a long lost past makes “Transcendental Realism” a significant work, not only for artists but anyone who senses the limitations of contemporary culture and strives to create a more vivid way of being.

| Quotations

from and/or photographs of Avatar Adi Da Samraj used by permission of the copyright

owner: © Copyrighted materials used with the permission of The Avataric Samrajya of Adidam Pty Ltd, as trustee for The Avataric Samrajya of Adidam. All rights reserved. None of these materials may be disseminated or otherwise used for any non-personal purpose without the prior agreement of the copyright owner. ADIDAM is a trademark of The Avataric Samrajya of Adidam Pty Ltd, as Trustee for the Avataric Samrajya of Adidam. Technical problems with our site? Let our webmaster know. |

Celia

Rabinovitch is an artist, writer, and teacher. Her paintings have been exhibited

in solo shows in Canada, the U.S.A. and Europe, including Quattro, a four person

international show in Vienna, Austria (2000) the Florence Biennale (1999) The

Grotto Cycle, California Institute of Integral Studies (2003); Industrial Romance,

University of San Francisco and Gallery, Winnipeg, YYZ, Toronto; Emily Carr Institute;

Plug-In and the Winnipeg Art Gallery. Her book,

Celia

Rabinovitch is an artist, writer, and teacher. Her paintings have been exhibited

in solo shows in Canada, the U.S.A. and Europe, including Quattro, a four person

international show in Vienna, Austria (2000) the Florence Biennale (1999) The

Grotto Cycle, California Institute of Integral Studies (2003); Industrial Romance,

University of San Francisco and Gallery, Winnipeg, YYZ, Toronto; Emily Carr Institute;

Plug-In and the Winnipeg Art Gallery. Her book,